Better Late than Never

From today’s RBA statement on official interest rates:

In future meetings, the Board will continue to evaluate whether the stance of policy will be sufficiently restrictive to return inflation to the 2-3 per cent target.

One would have hoped that the RBA might have performed this evaluation properly before inflation moved outside the target range.

posted on 05 February 2008 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

In Bed with Sharon Burrow

What do opposition Treasury spokesman Malcolm Turnbull and ACTU President Sharon Burrow have in common?

Mr Turnbull:

“I have said before and I will repeat again that I think there are powerful reasons for the Reserve Bank to hold its hand at this meeting.

“There is a lot going on in the international markets and we have inflation running at around that 3 per cent mark at the moment in Australia.”

Ms Burrow:

“It should wait and see on interest rates until the effect of the turmoil in the United States caused by the sub-prime housing market is clearer,” Ms Burrow said.

It is of course precisely the lack of interest rate rises from the RBA that has been the main cause of Australia’s inflation problem.

posted on 05 February 2008 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets, Politics

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

Australian versus US House Prices

The December quarter ABS established house price index saw the weighted average for capital cities rise 3.2% q/q and 12.3% y/y. Perth once again underperformed the other capital cities, with growth of 0.9% q/q and 1.1% y/y, coming down off the massive near 50% y/y growth rate seen for the year-ended in September 2006. Sydney rose 2.4% q/q and 8% y/y, giving a very respectable 5% y/y real return after headline inflation. All the other capitals recorded double-digit annual percentage gains in house prices, with house price growth in Melbourne, Brisbane and Adelaide standing around 20% annually.

For all the talk of a house price bust in Australia a few years ago, Sydney was the only state capital to record an outright decline in house prices at an annual rate, although Melbourne got close with a modest 0.4% y/y rate in the year to December 2004. Many of Australia’s capital cities did, however, experience house price disinflations that were far more dramatic than anything experienced in the US as part of its so-called housing ‘bubble.’

This raises the obvious question as to why house price swings in the US that are relatively modest by Australian standards have had much more adverse macroeconomic consequences in the US. The answer most probably lies in the distinctive features of the US mortgage market. The Australian market is much better conditioned to pronounced cycles in house prices, inflation and interest rates. The lesson is that dramatic house price disinflations or deflations in themselves need not be a serious macroeconomic problem. The more important issue is how these swings interact with, and get propagated through, the financial system.

Australia is a price-taker in global capital markets. The US is an effective price-maker, which means it has the capacity to export financial shocks that have their origins in the non-traded goods sector of the US economy. There has been some pass through of this shock to Australian retail lending rates, as Australian borrowers compete with the rest of the world for scarce liquidity. But this shock to retail lending rates can be traded-off against changes in official interest rates. It has long been argued that Australia’s negative net international investment position left it vulnerable to negative external financial shocks, but the current episode suggests that Australia’s vulnerability to international credit shocks has been greatly exaggerated.

posted on 04 February 2008 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

‘Unrepentant’

posted on 01 February 2008 by skirchner in Culture & Society, Economics, Financial Markets, Foreign Affairs & Defence, Higher Education, Misc, Politics

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

Peak Oil Nutters

The WSJ profiles some typical Peak Oilers:

It was around midnight one evening in November when Aaron Wissner shot up in bed, jolted awake by a fear: He wasn’t fully ready for the day when the world starts running low on oil.

Yes, he had tripled the size of the garden in front of the tidy white-clapboard house he shares with his wife and infant son. He had stacked bags of rice in his new pantry, stashed gold valued at $8,000 in his safe-deposit box and doubled the size of the propane tank in his yard.

“But I felt panicky, like I needed more insurance,” he says. So the 38-year-old middle-school computer teacher put on his jacket and drove to an all-night gas station, where he filled three, five-gallon jugs with gasoline.

“It was a feel-good moment,” says his wife, Kimberly Sager. “But he slept better.”

Not sure how a few bags of rice, a propane tank and a few grand in gold is meant to help with TEOCAWKI, but like they say, whatever helps you sleep at night.

At least someone is out there trying to give the peak oilers an education:

Three weeks after their first immersion, the couple drove to a peak-oil conference in Ohio, where lecturers showered them with statistics on demand curves and oil-field depletion rates. Then, at a conference in Denver, a man in a chicken suit called them crazies as he passed our fliers arguing that the world still has plenty of oil.

I’m with chicken suit guy.

posted on 26 January 2008 by skirchner in Culture & Society, Economics, Financial Markets

(2) Comments | Permalink | Main

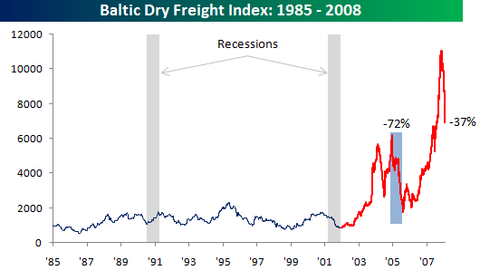

Who Killed the Baltic Dry Index?

The Baltic Dry Index gets a lot of attention as a leading indicator and the signal it’s sending at the moment is certainly bearish. The index is 37% off its peak, having recorded some of its biggest one-day declines in the history of the series dating back to 1985. But a number of caveats are in order.

First, the index is US dollar denominated, and the November peak coincided with the lows in the US dollar index. Since then, the Curse of the Economist Magazine Cover has worked its magic and the US dollar index is off its lows. So at least some of the decline can be attributed to straightforward valuation effects.

Second, the massive run-up in the index probably tells us as much about supply constraints in the international shipping industry as it does the demand for commodities. Like most people, the shipping industry was caught short by the global commodities boom and building extra capacity will take time.

Third, as the following chart from Bespoke Investment Group shows, while previous recessions have been preceded by a downturn in the index, there are many more downturns in the index than there are recessions, including a much more dramatic downturn in 2004-05.

posted on 24 January 2008 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

A Virtual Bank Run

Second Life suffers a real life banking system crisis:

the San Francisco company that runs the popular fantasy game pulled the plug on about a dozen pretend financial institutions that were funded with actual money from some of the 12 million registered users of Second Life. Linden Lab said the move was triggered by complaints that some of the virtual banks had reneged on promises to pay high returns on customer deposits…

The shutdown has caused a real-life bank run by Second Life depositors. Though some players managed to get their Linden dollars out, others are finding that they can no longer make withdrawals from the make-believe ATMs. As a result, they can’t exchange their Linden-dollar deposits back into real dollars. Linden officials won’t say how much money has been lost, but a run on another virtual bank in August may have cost Second Life depositors an estimated $750,000 in actual money.

The WSJ profiles one of the Second Lifers affected:

“Everyone thinks that because you’re losing play money, it excuses everything, but it’s convertible to real money,” says a Second Life player whose avatar is named UpMe Beam. On Sunday night, the female character was wandering topless through the virtual lobby of a Second Life bank called BCX Bank, where a sign said it was “not currently accepting deposits or paying interest.”

In real life, UpMe Beam is a man who says that he is a certified public accountant who has audited banks.

posted on 23 January 2008 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

Who Lost the ‘War on Inflation’?

The December quarter CPI is nothing less than disastrous. The 3.6% y/y average outcome for the statistical underlying measures is the worst result for underlying inflation since the great disinflation of the early 1990s and well above the 3.25% forecast in the RBA’s November Statement on Monetary Policy. It is sobering to recall that these measures are preferred by the RBA because they capture the persistent component of inflation that forecasts future inflation outcomes.

The government talks about a ‘war on inflation,’ but that war was lost by the RBA long before today’s CPI release. Amid all the finger-pointing between the federal government and opposition, few have bothered to point out that the Reserve Bank is the only public institution in Australia with a specific mandate to control inflation. Inflation is not some unfortunate exogenous event, unrelated to past monetary policy actions. The inflation target breach tells us that the RBA was not doing its job properly 12-18 months ago. In the US, the current and former Fed Chair are widely criticised for their supposed role in financial market problems not of their own making. Yet in Australia, the RBA’s senior officers still enjoy almost unimpeachable authority while at the same time failing to meet their core mandate.

If the RBA’s November Statement on Monetary Policy forecasts were realised, the RBA could perhaps have sat on its hands with a view to riding out the inflation target breach over the next 12 months and hope that international and domestic growth weaken sufficiently to return inflation to target in 2009. The risk in doing so is that the RBA ends up validating an acceleration in domestic inflation, requiring an even more aggressive tightening response down the track, with greater downside risks for the domestic economy. The tragedy of the RBA’s policy error on inflation is that it now has much less flexibility in responding to the deteriorating global growth outlook. The RBA can be expected to raise rates at its February Board meeting, despite continued equity market volatility and aggressive Fed easing.

posted on 23 January 2008 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(7) Comments | Permalink | Main

‘Fiscal Conservatism’ for All

Seems not everyone got the memo on ‘fiscal conservatism’:

KEVIN Rudd faces intensifying pressure from community groups for billions of dollars of new government spending, despite his promise of an austerity budget designed to ease pressure on inflation and interest rates.

As the Prime Minister told a business breakfast in Perth yesterday of his plans to cut spending in the 2008-09 budget, to be delivered in May, his office was being flooded with requests for more than $7 billion in spending on health, infrastructure and climate change.

posted on 22 January 2008 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets, Politics

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

How to be a ‘Fiscal Conservative,’ Without Really Trying

Prime Minister Kevin Rudd is promising budget surpluses of 1.5% of GDP, as part of the government’s ‘war on inflation.’ Relative to the forward estimates contained in the previous government’s Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook, this represents a fiscal contraction of a mere 0.2% of GDP.

Contrary to popular perception, Commonwealth fiscal policy is already the tightest it’s been in two decades. Looking at actual budget outcomes, as opposed to the forward estimates or the arbitrary counterfactuals the commentariat love to play with, the fiscal impulse (ie, the change in the budget balance as a share of GDP) has been either neutral or contractionary for the entire period since 2001-02. The underlying cash surplus has ranged between 1.5-1.6% of GDP since 2004-05, a GDP share not seen since the peak of the last cycle in the late 1980s. The automatic stabilisers would probably cough-up another surplus of 1.5% of GDP anyway, regardless of any contribution from discretionary policy actions.

The fiscal impulse has been largely irrelevant to inflation and interest rate outcomes in recent years. Today’s announcement suggests that is not about to change.

posted on 21 January 2008 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets, Politics

(1) Comments | Permalink | Main

Contrarian Indicator Alert: Mum & Dad Gold Bugs

The phones are running hot at the Perth Mint.

For an Australian dollar-denominated investor, gold should hold even less than usual appeal. As a major producer, Australia is already long gold. The Australian dollar is positively correlated with the US dollar gold price, so the Australian dollar gold price tends to underperform gains in the world price.

Little known fact: China became the world’s number one gold producer in 2007, according to GFMS Ltd’s annual Gold Survey.

posted on 21 January 2008 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

Paypal’s Exchange Rates

I regularly transfer US dollar Paypal balances to Australian dollars, which are normally converted at a 2.5% spread to wholesale spot rates. Paypal update their exchange rates twice daily. Since I have real-time access to wholesale spot rates, I can check the spread to spot and it is usually pretty close to 2.5%.

Recently, however, I have had a problem with Paypal failing to quote me updated exchange rates. I asked other Paypal account holders to get quotes on the USD-AUD exchange rate and they were being quoted different conversion rates that better reflected the 2.5% spread over spot rates.

I then checked to see what would happen if I logged into my account from a different computer, thinking it might be a caching issue. This finally resulted in an updated quote, but when I transferred a USD balance, the transfer was made at the former stale exchange rate I was being quoted previously.

Apart from being weird and different from my previous experience with Paypal, this is also inconsistent with Paypal’s Product Disclosure Statement required of financial service providers under Australian law. The exchange rate was not being updated regularly, the quoted spread was not the 2.5% mentioned in the PDS (at least not for me) and Paypal processed the conversions at a different rate to the one they quoted me immediately before I made the transaction.

My enquiries with Paypal have only elicited irrelevant boilerplate responses, so I’m thinking of referring the matter to the banking industry ombudsman. But before I do, I thought I would see if anyone else has had similar problems or had an explanation for what might be going on. I would actually be even more impressed to hear from someone with Paypal Australia. Any tech or financial journalists who would like to follow-up the story are also welcome to get in touch.

UPDATE (February 1): Paypal have finally acknowledged the error in an email to me:

We are actually aware of the issue and are working towards a resolution. We have added your account as another example of the error to expedite the urgency of the issue.

My suggestion would be that anyone with recent Paypal exchange rate conversions should check the rate they were given against wholesale spot rates. If the spread is not around 2.5%, you may want to get on to Paypal to seek a correction.

posted on 19 January 2008 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

Paypal Spot Rate Check Bleg

Would be grateful if any readers with a Paypal account and a USD balance could do a check on the USD-AUD exchange rate (not AUD-USD) quoted by Paypal. Note that there is no need to do an actual conversion, just go into ‘manage currency balances,’ where it will give you a quote without having to follow through with the conversion. I need the quote to five decimal places (try converting more than one US dollar to get the full quote). Potentially an interesting story in it. Will post a link from my site to yours as reward for your trouble. Thanks in advance. My email is info at institutional-economics.com.

UPDATE: No more quotes thanks. I have what I need.

posted on 18 January 2008 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

The CEO of Princeton Economics

Australia’s House Economics Committee may be cringe-inducing at times, but at least they generally know who they are talking to. Here’s Representative Marcy Kaptur, D-Ohio, grilling Fed Chairman Bernanke at a Budget committee hearing:

KAPTUR: Number three, seeing as how you were the former CEO of Goldman Sachs, what percentage level—oh, investment—were you not…

BERNANKE: No, you’re confusing me with the Treasury Secretary.

KAPTUR: I got the wrong firm?

BERNANKE: Yes.

KAPTUR: Paulson. Oh, OK. Where were you, sir?

BERNANKE: I was a CEO of the Princeton Economics Department.

KAPTUR: Oh, Princeton. Oh, all right. Sorry. Sorry.

(LAUGHTER)

Also caught on Youtube.

posted on 18 January 2008 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

A Monetarist’s Work is Never Done

At the ripe old age of 92, Anna Schwartz is still giving the Fed a hard time:

“There never would have been a sub-prime mortgage crisis if the Fed had been alert. This is something Alan Greenspan must answer for,” she says.

While this is a widely held view, it is one I (respectfully, in this case) disagree with. It is hard to pin the under-pricing of risk in credit markets on monetary policy, as opposed to the innovative nature of the products involved. One can make a case that the amplitude of the most recent Fed funds rate cycle has been a factor in triggering widespread mortgage defaults, but that in turn reflected the preponderance of fixed rate mortgages in the US, which delayed the pass through of changes in the Fed funds rate to actual lending rates. The Fed was simply not getting much of an effect from changes in the Fed funds rate back in 2002 and 2003, which was also a factor in the very gradual re-tightening from mid-2004. If anything, this suggests that the US economy is not all that responsive to changes in official interest rates. The Fed stopped tightening and held rates steady for more than a year before the problems in credit markets emerged. It is hard to believe that the Fed triggered a credit shock by doing nothing for more than 12 months.

Few of the people who are now blaming the Fed were complaining about low interest rates in 2003. For its part, the Fed was fretting over the prospect of deflation instead. As the linked story notes:

Bernanke insists that the Fed has leant the lesson from the catastrophic errors of the 1930s. At the late Milton Friedman’s 90th birthday party, he apologised for the sins of his institutional forefathers. “Yes, we did it, we’re very sorry, we won’t do it again.”

Of course, there is no reason why we shouldn’t revise our analysis of events ex-post. But to blame subsequent events entirely on monetary policy is as unhelpful as it is implausible.

Still, you’ve got to hand it to Anna, fronting up to work at the NBER at 92. Most of us should be grateful to still be constructing coherent sentences at that age. If Friedman and Schwartz are any guide, monetarism is good for your health.

posted on 17 January 2008 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(3) Comments | Permalink | Main

Page 30 of 45 pages ‹ First < 28 29 30 31 32 > Last ›

|